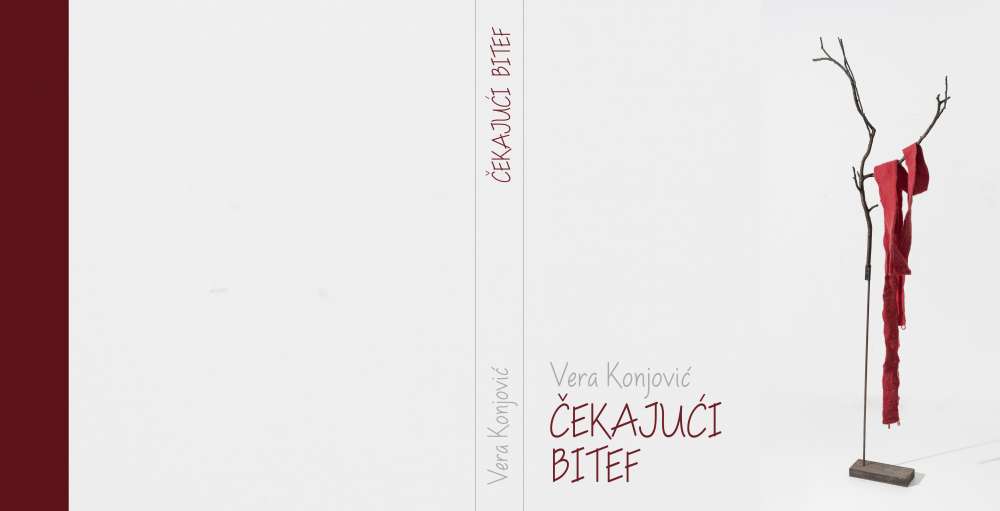

Vera Konjović’s book Waiting for BITEF is a remarkable testimony to the creation and duration of the world theatre in Belgrade. Conceived as a triumphant farewell to an important segment of Bitef Festival - Bitef on Film, in which the author of the book directly and devotedly participated as its artistic creator and often as the programme producer too, the book Waiting for BITEF mentions absolutely all the events and all the people that have made Bitef unique and internationally relevant. One could say that this delving into the depths was expected since Vera Konjović participated in everything that surrounded Bitef from the very beginning, at first inconspicuously, accepting various responsibilities, getting increasingly involved over time, but always with an exceptional devotion and commitment to the values of the event that Mira Trailović and Jovan Ćirilov created.

The fragmentary notes by the author have turned the book Waiting for BITEF into a unique autobiography of others, in the most positive sense of the genre, in the spirit of Borislav Mihajlović Mihiz. Trying to neither omit anything or forget anyone who has ever come and stayed in Belgrade because of the festival, Vera Konjović has brought to life one world whose art and uniqueness are slowly fading in the memories of those who participated in the ceremonial which to the younger generations seems as a tale of yore. The testimony which broke loose under the covers of Bitef on Film caused this book, although small and personal, to become an important anthology of Bitef duration. Yet another aspect of the book Waiting for BITEF that makes it a remarkably important read is the author’s language which, simple and appealing, makes the curious reader sail smoothly through the meanders of Bitef events and stories hoping for the pleasure of knowing to last as long as the Bitef Festival itself.

Waiting for BITEF is unquestionably an important work of literature, not only because of the power of the text, but also because of the serious approach in the creation of the book which, alongside the text, ample photo-documentation, a selection of newspapers articles and the index of names reconfirms the international reputation of Bitef.

Miloš Latinović, the Director of Bitef Theatre

Author:

Vera Konjović (excerpts from the book Waiting for BITEF)

“In 1976, we celebrated ten exciting years of Bitef. That Bitef was festive both in number and in the quality of programmes, but also by the fame of the participants. Moreover, the Theatre of Nations took place that year, too.

Mira Trailović and Jovan Ćirilov did not think that was enough, though, so they gave it some thought, and came up with the idea to add another programme - a selection of films related to theatre. I worked in the film industry at the time, in the festival Fest, as a programme producer, I used to hang around theatres, to translate Slovenian performances at Bitef, I was friends with Mira and Jovan, which might have been the reasons why they spontaneously picked me to put that idea into practice.

The programme achieved unexpected success, so Bitef on Film turned into a regular side programme. It lasted for 40 years.

…

Gledališče, Schauspielhaus, szinház, pozorište, theatre - words which, in the languages that I speak, denote the institution I am fond of.

I spent my early childhood in Kranj, in 22 Jezerska cesta, the street that was leading towards the castle Brdo which my grandma’s cousin sold to Prince Regent Pavle in 1935. I was a scrawny child, always pecking at my food, so my mother took me to see a doctor. He asked if we had any food at home. Stunned, my mother said: “Plenty.” A diagnosis followed: “When there’s plenty of food in the house, children don’t die of hunger.” I would spend hours sitting at the table, stubbornly refusing some food.

…

In the autumn of 1940, my friends started school. I was the youngest and - oh, the horror and humiliation! - I was not accepted to school. I used to meet the first graders and tried to study with them. They would demean me, which made the situation even more tragic. A month later, my mother went to the newly built school, one of the most modern ones in Slovenia, and asked them to bend the rules and let me come for a day or two because it worried her how miserable I was. I was fidgety, there was no way I would manage to sit still. They reluctantly agreed. A week later, they asked for my documents, so I became a regular pupil. I was fidgety, true, but also the best in my class.

My dad, a reserve officer with the Yugoslav army, was mobilized in 1941. German forces entered Kranj. The SS-divisions needed rich, luxurious apartments for their officers, so my mom and I got interned. Fortunately, we were in the first group which was sent to Smederevska Palanka in Serbia, and not to Germany. There could be only one suitcase per room. My mom had one for both of us, while I was small and carried a small backpack and a teddy bear in my hands. She was the number 187, and I was 188.

My paternal grandma was rich. She paid a lavish sum to people smugglers to take us from the German occupation zone into the Hungarian zone, to Novi Sad. The first attempt failed, the second succeeded. We went to Budapest straight away and spent three months there waiting to have our fake IDs made. We returned to Novi Sad on the eve of the infamous raid. Thanks to our neighbors, the Bères family, Hungarians, we stayed alive. In February, when there was no longer blood on the streets and no remains of human brains on the houses, I started school - a Hungarian one. Some objected, but my mom responded: “The more languages you know, the more of a person you are. She’ll have learned Hungarian before they go down.” I refused to start the first grade all over again. I was an excellent pupil, so I did not want to be retained. They tried persuading me that the schoolyear had already started, that I did not speak Hungarian… I was stubborn again. They gave in. Two months later, I was speaking Hungarian like a Hungarian, and I ended the schoolyear with straight As.

In March 1944, all the strategic points in Hungary were taken by the German forces. Our friends organized for my mom to be detained by the Hungarians and taken to the prison in Budapest, so that the Germans, from whose camp she had escaped, would not get a hold of her. I stayed in Novi Sad, together with our longstanding maid Piros, who got married and, swayed by her husband, took everything she liked from the house… When the bombing of Budapest began, all the prison guards ran away, and the prisoners broke out of the prison. My mom took a train to Novi Sad. She spent more time lying in the corn fields under the bombers than travelling. She arrived a couple of days later, out of her wits, and found me in a miserable state.

In October 1944, we were liberated from the Hungarians and the Germans, but also from many other things.

…

I started Grammar school. They were confused that I, who was speaking Serbian with a strong Hungarian accent, did not go to a Hungarian school. I had trouble pronouncing the sounds “ć” and “č”, and “đ” and “dž”. I was no longer a little girl, so learning a new language went at a slower pace, and only at the end of the schoolyear did I become a Serbian. Back then, Russian was mandatory throughout schooling. I studied it until the end of my high-school graduation. In the fifth grade, I took up English as my second foreign language - it was popular and fashionable back then.

At the beginning of the 1950ies, Novi Sad did not have a university, so I studied in Belgrade. I chose Italian as a second language, the one that we listened to for two semesters. I never learned either Russian or Italian.

…

I used to work in the Matica Srpska Library, where I learned a lot about books and from books, in Avala Film I learned how movies are made, in Jugoslavijapublik what economy is and what bad human relations are, in the Festival of Yugoslav Film I got to know Yugoslav cinema and Yugoslav filmmakers. In Fest, which was initially a part of Yugoslavia Film, and then of Beograd publik, which employed people from all walks of life, I met stars and starlets from the whole world, while from Zvezda Film, where I worked my head off like in all the other places where I worked, but also travelled a lot, I escaped into the retirement after the arrival of a new director who didn’t know anything about cinema, because I was afraid I might have to pay for his sins. Once retired, I started translating more. And, I should not forget mentioning because it is important: Bitef is a part of my life without which it would be poorer.”